Quick Look

Grade Level: 4 (3-5)

Time Required: 45 minutes

Lesson Dependency: None

Subject Areas: Algebra, Physical Science

NGSS Performance Expectations:

| 4-PS3-2 |

Summary

Students explore the phenomenon of electricity as they learn about current electricity and necessary conditions for the existence of an electric current. To make sense of this phenomenon, students construct a simple electric circuit and galvanic cell to help them understand voltage, current, and resistance. They also use the disciplinary core ideas of energy and electric current to better understand the crosscutting concept of energy transfer.Engineering Connection

An understanding of electric circuits and the concepts of voltage, current and resistance enables engineers to design all sorts of useful devices and inventions that improve our lives. For example, engineers designed photovoltaic (PV) cells, commonly called solar cells, which use sunlight to make electricity. No matter what the source of the electrical power, engineers apply their understanding of how current electricity works to make devices that run the appliances and equipment that are important in our everyday lives.

Learning Objectives

After this lesson, students should be able to:

- Understand the concept of current electricity, and the relationship between current, voltage and resistance.

- Recognize that electrical energy in an electric circuit can be converted to different forms of energy, such as motion, thermal and light energy.

- List alternative sources of electricity.

- Recognize that engineers apply their understanding of how electricity works to design appliances and equipment that are important in our everyday lives.

Educational Standards

Each TeachEngineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science,

technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in TeachEngineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN),

a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics;

within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

Each TeachEngineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in TeachEngineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN), a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics; within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards - Science

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

4-PS3-2. Make observations to provide evidence that energy can be transferred from place to place by sound, light, heat, and electric currents. (Grade 4) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This lesson focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Make observations to produce data to serve as the basis for evidence for an explanation of a phenomenon or test a design solution. Alignment agreement: | Energy can be moved from place to place by moving objects or through sound, light, or electric currents. Alignment agreement: Energy is present whenever there are moving objects, sound, light, or heat. When objects collide, energy can be transferred from one object to another, thereby changing their motion. In such collisions, some energy is typically also transferred to the surrounding air; as a result, the air gets heated and sound is produced.Alignment agreement: Light also transfers energy from place to place.Alignment agreement: Energy can also be transferred from place to place by electric currents, which can then be used locally to produce motion, sound, heat, or light. The currents may have been produced to begin with by transforming the energy of motion into electrical energy.Alignment agreement: | Energy can be transferred in various ways and between objects. Alignment agreement: |

Common Core State Standards - Math

-

Determine the unknown whole number in a multiplication or division equation relating three whole numbers.

(Grade

3)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use decimal notation for fractions with denominators 10 or 100.

(Grade

4)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association - Technology

-

Tools, machines, products, and systems use energy in order to do work.

(Grades

3 -

5)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Explain how various relationships can exist between technology and engineering and other content areas.

(Grades

3 -

5)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

State Standards

Colorado - Math

-

Find the unknown in simple equations.

(Grade

4)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Colorado - Science

-

Show that electricity in circuits requires a complete loop through which current can pass

(Grade

4)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Describe the energy transformation that takes place in electrical circuits where light, heat, sound, and magnetic effects are produced

(Grade

4)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Pre-Req Knowledge

Students should be familiar with the concepts of atoms, electrons, and electric charge.

Introduction/Motivation

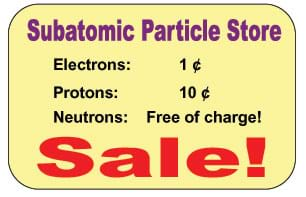

Ask the students: Have you ever had to replace the batteries in a flashlight? (Many will answer yes.). Why did you have to replace the batteries? (Possible answers: The batteries were dead, the flashlight did not work or the light was dim.) Once you place new batteries in the flashlight, you complete an electric circuit and the flashlight operates and the light shines brightly. Remind students that atoms are made of smaller parts called protons, neutrons and electrons. The electrons can carry a negative electric charge and can move from atom to atom and create current electricity. Tell students that during this lesson, they will learn how the electrons' charge can help light a bulb in a flashlight and what is trying to stop charge from lighting the bulb!

If you look closely at a battery, you will see a small number with the letter "V" next to it. Does anyone know what the letter represents? (Answer: Volts.) Let students know that during this lesson, they will find out what volts have to do with charge in a circuit.

Ask the students: Does anyone know of any alternatives to generating current electricity at a power plant? (Possible answers: Photovoltaic cells/solar cells, wind farms.) Photovoltaic (PV) cells, commonly called solar cells, have been powering satellites in space for decades. Most people have seen solar cells on calculators, and on road signs and lights along highways. Photovoltaic cells use sunlight to make electricity. Using photovoltaic cells to produce electricity does not produce the polluting emissions that conventional power plants produce. Conventional fossil fuels require costly operations to extract, while sunlight is freely available everywhere. Unfortunately, photovoltaic cells are still expensive to manufacture (and require non-solar power to manufacture!). Engineers and scientists are working to make solar electricity affordable for everyone. They're also working on new applications for photovoltaic cells, such as solar-powered roads and wearable solar technology.

Lesson Background and Concepts for Teachers

Electrical Potential Energy and Voltage

The force between any two charges depends on both the product of the charges and the distance between them. The force between two like-charged objects is repulsive, whereas the force between two oppositely-charged objects is attractive. Therefore, it takes energy to push two like-charged objects together or to pull two unlike-charged objects apart. For example, if we were to take two negatively-charged objects and compare the energy required to hold them at different distances from each other, we would find that the amount of energy we need to expend is increased as we bring the two negatively-charged objects closer together. This is analogous to the effect you experience when trying to push the like poles of two magnets together.

The closer together the two like-charged objects are (or the farther apart two oppositely-charged objects are) the more electrical potential energy they have. The amount of electrical potential energy per charge is called the voltage. It may be helpful to present voltage as the "electrical pressure" that causes the electrons to move in a conductor. If electric current is analogous to water moving in a pipe, then electrical pressure (voltage) is analogous to water pressure in a pipe. A pump in a water line would be analogous to a voltage source. Batteries, generators, photovoltaic cells and other voltage sources all provide electrical energy that can be used to do work.

The SI unit (SI is the abbreviation for the International System of measurement from the French Système Internationale) of electrical potential, or voltage, is the volt [V]. Small batteries have voltages ranging from 1.5 V to 9 V. This means that there is a potential difference of 1.5 V across the terminals of the battery. The electric outlets in homes provide electricity at 120 V or 220 V. Power lines are at 10,000 V, or higher, in order to reduce energy losses due to the resistance of the transmission cables.

Charge Moves Due to a Voltage Difference

There is a flow of electric charge, an electric current, if the ends of a conducting wire are held across a voltage source (potential difference). The "electrical pressure" due to the difference in voltage between the positive and negative terminals of a battery causes the charge (electrons) to move from the positive terminal to the negative terminal. The voltage difference, also known as a voltage drop, is produced by attaching, for example, a light bulb or radio to the battery. A voltage source, such as a battery, generator or photovoltaic cell, can provide the sustained "electrical pressure" required to maintain a current. Current is measured in amperes (or amps) [A], in the SI system. One amp is the flow of 6.25 x 1018 electrons per second.

Circuits

Any path through which charges can move is called an electric circuit. If there is a break in the path, there cannot be a current; such a circuit is called an open circuit. However, if the path for movement of charge is complete, then the circuit is closed. There can only be a current in a closed circuit. Electrons cannot pile up or disappear in a circuit. A circuit can be as simple as a wire connected to both terminals of a battery, or as complicated as an integrated circuit in a home computer. Refer to the Completing the Circuit activity to help students illustrate the difference between an open and closed circuit.

Resistance, Conductors and Insulators

Different materials oppose the movement of charge to varying degrees. The resistance of an object is a measurement of the degree of opposition to charge movement within that object. Conductors (such as metals) have lower resistances while insulators (such as wood or plastic) have higher resistances. An object's resistance depends on the materials that make up the object, its length, cross-sectional area and temperature.

If we continue with the water analogy for electric current, we can think of the resistance of a material like the boulders in a river, which slow the flow of water. Two objects made of the same material can have different resistances if their physical dimensions are different. Water in a wide riverbed (or a hose with a large diameter) has less resistance to flow than water in a narrow riverbed (or a hose with a small diameter). The resistance of a thick copper wire is less than the resistance of a thin copper wire. Longer pieces of a material have greater resistances than shorter pieces. Thus, we can see that the resistance to charge movement is cumulative in a material. Finally, lowering a material's temperature decreases its resistance. The SI unit of resistance is the ohm [Ω], which is equal to one volt per amp [V/A].

It is important to note that any material can conduct electricity if there is a high enough voltage across it. This is what happens both in lightning and electrocution. Air is normally an insulator, but during thunderstorms, a very high electrical potential difference between the clouds and the ground forces a current through the air briefly. In the body, the skin acts as an electrical insulator. When there is a high voltage across the body, there is a brief discharge through the body, damaging the tissues and possibly causing death. The likelihood of electrocution is increased if the skin is wet. This is because salts (from perspiration or soils) on the body dissolve in the water, producing a conducting solution.

Current, Voltage and Resistance Relationships

The current in a circuit is directly proportional to the voltage across the circuit and inversely proportional to the resistance of the circuit. This relationship is called Ohm's law. For a given voltage, there is greater current in a circuit element with a lower relative resistance. Also, for a given resistance, there is greater current in a circuit element if there is a greater voltage across it. The following equations, Ohm's law, describe the relationship:

I = V / R

or

V = I * R

Where I is current, V is voltage and R is resistance. For example, if a flashlight with a pair of alkaline batteries at a total of 2 V has a light bulb with a resistance of 10 ohms. What is the current? (Answer: I = V / R = 0.2 A.)

How Do Batteries Work?

In a battery, chemical energy is converted to electrical energy. Whenever a battery is connected in a closed circuit, a chemical reaction inside the battery produces electrons. The electrons produced in this reaction collect on the negative terminal of the battery. Next, electrons move from the negative terminal, through the circuit, and back to the positive battery terminal. Without a good conductor connecting the negative and positive terminals of the battery, the chemical reaction that produces electrons would not occur.

There are many different types of batteries, each using different materials in the chemical reaction and each producing a different voltage. A battery is actually several galvanic cells (a device in which chemical energy is converted to electrical energy) connected together. Every cell has two electrodes, the anode and cathode, and an electrolyte solution. Electrons are produced in the reaction at the anode, while electrons are used in the reaction at the cathode. The electrolyte solution allows ions to move between the cathode and the anode where they are involved in chemical reactions balancing the movement of electrons.

Possibly the most familiar battery reaction takes place in a car battery. This reaction involves the disintegration of lead in sulfuric acid. In a lead-acid battery, each cell has two lead grids, one filled with spongy lead and one filled with lead oxide, immersed in sulfuric acid. The grid with spongy lead is the anode: electrons are produced as the lead reacts with sulfuric acid. These electrons collect on the negative terminal of the battery. The grid with lead oxide is the cathode in a lead-acid battery. Electrons that have gone through the circuit and returned to the cathode are used in a reaction that takes place at the cathode. Each cell produces 2 V. In a car battery, there are six of these lead-acid cells linked together in series to produce a total voltage of 12 V.

The lead-acid cell is called a wet cell because the reaction takes place in a liquid electrolyte. Dry cells have a moist, pasty electrolyte. Most batteries used in consumer electronics are dry cells. Alkaline batteries are dry cells that use zinc and manganese-oxide electrodes with a basic (pH greater than 7) electrolyte. In inexpensive batteries, there is usually an acid electrolyte with zinc and carbon electrodes. Refer to the Two-Cell Battery activity for students to build a two-cell battery and test it using different electrolyte solutions.

Engineers, who design computers, cars, cell phones, satellites, spacecraft, portable electronic devices, etc., must understand batteries because they are integral to a device's functioning. Batteries are also used to store the energy generated from solar electric panels and wind turbines. Many engineers are working to develop batteries that last longer, are more efficient, weigh less, are less harmful to the environment, require less maintenance and/or are more powerful.

Associated Activities

- Completing the Circuit - Students use a battery, wire, small light bulb and light bulb holder to learn the difference between an open and closed circuit.

- Two-Cell Battery - Students build a two-cell battery and test it using different electrolyte solutions.

Lesson Closure

Ask students to give examples of devices that use current electricity. Have the students categorize the devices by the source of electricity, whether from solar cells, typical chemical batteries, a wall outlet (ultimately from a power plant) or a portable generator. Ask students to list some advantages and disadvantages of using the different power sources. As a class, discuss the functions of various devices, paying attention to the role of current electricity and the transformations of energy in the device. For example, contrast the use of current electricity to power a lamp and a fan. (The electricity is converted to light in the lamp, and to the movement of the blades in the fan.)

Vocabulary/Definitions

anode: An electrode at which oxidation occurs, producing free electrons that move to the cathode.

battery: One or more galvanic cells connected in series.

cathode: An electrode at which reduction occurs.

circuit: Any path along which electrons can move.

closed circuit: A circuit with a complete path, which allows for charge movement.

current: The flow of electric charge.

electrolyte: A material that dissolves in water, producing a solution that conducts electricity.

galvanic cell: A device in which chemical energy is converted to electrical energy in a spontaneous oxidation-reduction reaction.

ion: An atom or a group of atoms that has acquired a net electric charge by gaining or losing one or more electrons

open circuit: A circuit with a break in the path.

resistance: Opposition to the movement of electric charge.

semiconductor: A material that is usually insulating, but that becomes conducting through the addition of certain impurities.

voltage: The difference in electrical potential between two points in a circuit.

Assessment

Pre-Lesson Assessment

Brainstorming: In small groups, have students engage in open discussion. Remind students that in brainstorming, no idea or suggestion is "silly." All ideas should be respectfully heard. Encourage wild ideas and discourage criticism of ideas. Ask the students:

- From where does electricity come? (Possible answers: A wall outlet, a power plant, photovoltaic/solar cells, batteries, wind, etc.)

Know / Want to Know / Learn (KWL) Chart: Before the lesson, ask students to write down in the top left corner of a piece of paper (or as a group on the board) under the title, Know, all the things they know about electricity. Next, in the top right corner under the title, Want to Know, ask students to write down anything they want to know about electricity. After the lesson, ask students to list in the bottom half of the page under the title, Learned, all of the things that they have learned about electricity.

Post-Introduction Assessment

Discussion Question: Solicit, integrate, and summarize student responses.

- Engineers develop alternative sources of energy. Hold your hand up if you have ever used a solar-powered device. What are some different devices that use solar power? List types of devices on the board. (Examples: Calculators, radios, landscape lights, exterior house lights, lights at emergency highway telephones, roof-top collectors that heat household water, satellites, etc.)

Lesson Summary Assessment

Numbered Heads: Divide the class into teams of three to five. Have students on each team number off so each member has a different number. Ask the students one of the questions below (give them a time frame for solving it, if desired). The members of each team should work together to answer the question. Everyone on the team must know the answer. Call a number at random. Students with that number should raise their hands to give the answer. If not all the students with that number raise their hands, allow the teams to work a little longer. Ask the students:

- What can carry a negative electric charge, and move from atom to atom to create current electricity? (Answer: Electrons.)

- Why do most people not have solar panels on their houses? (Answer: Too expensive.)

- There cannot be current in an open circuit or a closed circuit? (Answer: Open circuit.)

- On a battery, what does the letter V represent? (Answer: Volts.)

- What type of energy in a battery is converted to electrical energy in a circuit: Light, mechanical, chemical or heat? (Answer: Chemical.)

- Write the equation V = I * R on the board. The current in a 10 Ω toaster is 11 A. What is the voltage of the circuit? (Answer: V = I * R = 110 V)

Know / Want to Know / Learn (KWL) Chart: Finish the remaining section of the KWL Chart as described in the Pre-Lesson Assessment section. After the lesson, ask students to list in the bottom half of the page under the title, Learned, all of the things that they have learned about electricity.

Lesson Extension Activities

Have students learn more about solar cells by conducting an Internet search. Photovoltaic cells can only be made of certain materials, called semiconductors, which are between conductors and insulators in their ability to conduct electricity. Silicon is the most commonly used semiconductor in photovoltaic cells. Whenever light hits a PV cell, some of the energy is absorbed by the cell. This energy can knock electrons loose from the atoms that make up the semiconductor material. An electrical device on the PV cell forces these loose electrons to move in a particular direction, thus creating an electric current. Metal contacts at the top and bottom of a photovoltaic cell, like the terminals on a battery, connect the PV cell to an electric circuit. This "circuit" may be the electrical system of a building or a single device. PV cells produce direct current (DC), current in one direction only, just like a battery. Most household appliances use alternating current: alternating current (AC) changes direction 60 times per second and is used in the U.S. The direct current from a PV cell can be modified to produce alternating current so it can be used by any electrical appliance. PV cells can be linked together in different ways to make panels for various applications. The photovoltaic system for a home might require a dozen panels while a calculator may have only one PV cell. For more information on photovoltaic cells, see: http://www.howstuffworks.com/solar-cell.htm.

Have students learn more about solar panels and systems by conducting an Internet search to find companies that make or sell photovoltaic (PV) panels. What are the typical costs of a solar panel? What are some applications? (Possible answers: Rural electrification, pumping water, electricity for homes and businesses.) Have students find out which parts of the world are the best for using photovoltaic systems to produce electricity. Where are the largest PV systems?

What is Volta's Pile? (Answer: A famous experiment by Alessandro Volta in 1800 that produced electricity by chemical means and spurred intense research in the field of electricity.) Have students investigate and build a variation of Volta's Pile. See instructions at: http://www.funsci.com/fun3_en/electro/electro.htm

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things TeachEngineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!More Curriculum Like This

Students are introduced to several key concepts of electronic circuits. They learn about some of the physics behind circuits, the key components in a circuit and their pervasiveness in our homes and everyday lives.

Students learn that charge movement through a circuit depends on the resistance and arrangement of the circuit components. In one associated hands-on activity, students build and investigate the characteristics of series circuits. In another activity, students design and build flashlights.

Students are introduced to the idea of electrical energy. They learn about the relationships between charge, voltage, current and resistance. In the associated activities, students learn how a circuit works and test materials to see if they conduct electricity.

References

Guyton M.D., Arthur, C. and Hall, John E., Textbook of Medical Physiology. 10th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: W B Saunders., 2000.

Hewitt, Paul G. Conceptual Physics. 8th Edition. New York, NY: Addison Publishing Company, 1998.

How Batteries Work, How Stuff Works, Inc., Media Network, accessed March 2004. http://www.howstuffworks.com/battery.htm

How Solar Cells Work, How Stuff Works, Inc., Media Network, accessed March 2004. http://www.howstuffworks.com/solar-cell.htm

Richardson, L. (2019, April 1). Solar Technology: What's the Latest Breakthrough? Retrieved October 02, 2020, from https://news.energysage.com/solar-panel-technology-advances-solar-energy

Copyright

© 2004 by Regents of the University of Colorado.Contributors

Xochitl Zamora Thompson; Sabre Duren; Joe Friedrichsen; Daria Kotys-Schwartz; Malinda Schaefer Zarske; Denise CarlsonSupporting Program

Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado BoulderAcknowledgements

The contents of this digital library curriculum were developed under a grant from the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), U.S. Department of Education and National Science Foundation GK-12 grant no. 0338326. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department of Education or National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: October 2, 2020

User Comments & Tips