Quick Look

Grade Level: 9 (9-12)

Time Required: 2 hours 30 minutes

Suggest 30 minutes for a short concept review and a practice example, then 120 minutes for the project

Expendable Cost/Group: US $5.00

Group Size: 4

Activity Dependency: None

Subject Areas: Algebra, Number and Operations, Physical Science, Physics, Problem Solving, Reasoning and Proof

NGSS Performance Expectations:

| HS-ETS1-2 |

| HS-ETS1-3 |

Summary

Students are introduced to static equilibrium by learning how forces and torques are balanced in a well-designed engineering structure. A tower crane is presented as a simplified two-dimensional case. Using Popsicle sticks and hot glue, student teams design, build and test a simple tower crane model according to these principles, ending with a team competition.

Engineering Connection

Having an understanding of equilibrium is critical for engineers and scientists. Buildings, bridges, and other structures remain standing because engineers design them to meet equilibrium conditions, in which all of the forces acting on the structures are balanced.

Learning Objectives

After this activity, students should be able to:

- Understand the concept of static equilibrium.

- Identify and model, with free-body diagrams, forces in two dimensions (x-y plane) and torques about a point.

- Model why and how equilibrium occurs for a two-dimensional shape.

- Understand how forces and torques must sum to zero in order for an object to remain in static equilibrium.

- Use multiple equations to solve for unknown variables.

Educational Standards

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science,

technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN),

a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics;

within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN), a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics; within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards - Science

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

HS-ETS1-2. Design a solution to a complex real-world problem by breaking it down into smaller, more manageable problems that can be solved through engineering. (Grades 9 - 12) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Design a solution to a complex real-world problem, based on scientific knowledge, student-generated sources of evidence, prioritized criteria, and tradeoff considerations. Alignment agreement: | Criteria may need to be broken down into simpler ones that can be approached systematically, and decisions about the priority of certain criteria over others (trade-offs) may be needed. Alignment agreement: | |

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

HS-ETS1-3. Evaluate a solution to a complex real-world problem based on prioritized criteria and trade-offs that account for a range of constraints, including cost, safety, reliability, and aesthetics, as well as possible social, cultural, and environmental impacts. (Grades 9 - 12) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Evaluate a solution to a complex real-world problem, based on scientific knowledge, student-generated sources of evidence, prioritized criteria, and tradeoff considerations. Alignment agreement: | When evaluating solutions it is important to take into account a range of constraints including cost, safety, reliability and aesthetics and to consider social, cultural and environmental impacts. Alignment agreement: | New technologies can have deep impacts on society and the environment, including some that were not anticipated. Analysis of costs and benefits is a critical aspect of decisions about technology. Alignment agreement: |

Common Core State Standards - Math

-

(+) Solve problems involving velocity and other quantities that can be represented by vectors.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association - Technology

-

Illustrate principles, elements, and factors of design.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

State Standards

Colorado - Math

-

Use units as a way to understand problems and to guide the solution of multi-step problems.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Solve systems of linear equations exactly and approximately, focusing on pairs of linear equations in two variables.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Solve linear equations and inequalities in one variable, including equations with coefficients represented by letters.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Colorado - Science

-

Develop, communicate and justify an evidence-based analysis of the forces acting on an object and the resultant acceleration produced by a net force

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Materials List

Each group needs:

- Popsicle sticks, ~150

- hot glue gun and glue sticks

- foam-core board base, 6.5 x 6.5 inch (16.5 x 16.5 cm)

- washers, coins or similar small objects (to use as weights)

- small paper cup (to hold weights)

- string (to hang cup from end of crane), ~1 ft (~30 cm)

- Static Problems Worksheet, one per student

- Competition Requirements

- (optional) Survey, one per student

For the entire class to share:

- textbook (or other weighty object) for the teacher torque demonstration described in the Introduction/Motivation section

- a counterweight made from: a small paper cup; washers, coins or similar objects (to use as weights); and string (~1 ft or ~30 cm) (see instructions in Procedure section)

- meter stick (to measure deflection of cranes at the end)

- three-bar balance (or any balance or scale)

- (optional) prize for winning team, such as lollipops or candy

Worksheets and Attachments

Visit [www.teachengineering.org/activities/view/cub_staticcrane_activity1] to print or download.Pre-Req Knowledge

Ability to solve simple algebraic equations

Introduction/Motivation

(Have nearby a textbook or other weighty object for a quick demo. Also have copies of the Static Problems Worksheet ready to hand out to students.)

What are forces? (Listen to student answers. May include technical terms, but look for everyday words such as "push" or "pull.")

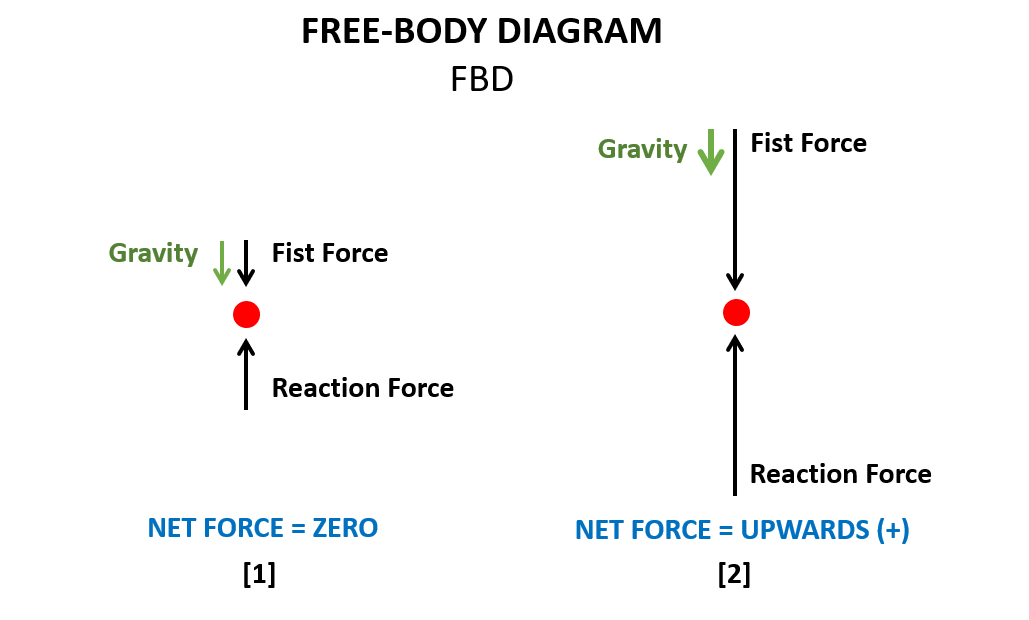

(Conduct a simple demonstration. Push your fist into a tabletop.) Why is my hand not going through the table? (Listen to student answers.) It is because the table "pushes back" with the same force I am applying down. This is called a reaction force, as in "for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction." The sum of forces from my fist and the table cause an upward acceleration due to the table being stationary. However, because gravity is also acting on my fist, we do not see this upward acceleration until enough force is applied to overcome the gravitational force acting downwards.

The best way to visualize this is to draw what is called a free-body diagram (or FBD). (Draw on the board a FBD of your fist and the forces acting on it; as shown in Figure 2.) In this case, the total forces acting on my fist cancel each other out; the sum of these forces is zero [1]. However, if I applied more force onto the table my fist would experience a net positive (upwards) force after having overcome gravity [2].

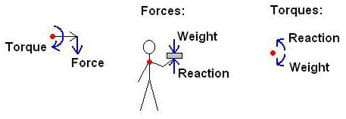

(Conduct another simple demonstration. Ask for a volunteer to come up to the front of the room. Ask the student to reach out with his/her strongest arm fully extended. Then place a textbook or other weighty object in his/her outstretched hand.) What is your body tending to do? (Listen to the student's response. Provide the correct response.) The weight of the book is causing your body to rotate to the left/right (in the direction of the hand holding the book). Now slowly bring the text book closer to your body. As you do this, tell us, is easier or harder to hold up the textbook as you do this?

Does anyone know what torque is? Torque is a force applied at a distance (torque = force * lever arm). Similar to the balance of forces, torques acting on a body must also sum to zero in order for the body to be in static equilibrium. (Draw another FBD on the board showing the torques about the volunteer student's shoulder, as shown in Figure 3. Sum the two opposing torques: the torque created by the weight of the book, as well as the torque that the student's arm is producing to counteract it. Write on the board: reaction torque - weight torque = 0. Counter-clockwise rotation or torque is positive; clockwise is negative.)

(With the class, work through one of the worksheet problems as an example of using the equations for net force and torque to demonstrate how to solve for an unknown force or torque.)

Ancient Greeks developed the first crane, a pulley system used to lift heavy loads. Today, many different types of cranes are used for different activities, such as loading or unloading freight from railroad cars or ships, or to move building materials at construction sites. A commonly seen type of crane is the tower crane, which is what we will build today. The tower crane is a type of balance crane that uses balancing weights in order to carry heavy loads. Tower cranes offer the best combination of height and lifting capacity, and thus are typically used in the construction of large buildings.

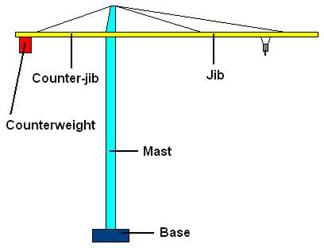

The main parts of a tower crane are the base, mast, jib (also called the working arm), and counter-jib (see Figure 4). The base is fixed to the ground or to a nearby building. The mast, attached to the base, gives the crane its height. The jib is the part of the crane that carries the load, and the counter-jib carries a counterweight to help balance the crane. When the load and the counterweight are properly balanced with the weight of the crane's arms (so that the forces sum to zero and the torques sum to zero), the crane is in static equilibrium. To balance the torques, a heavier counterweight is used on the shorter side of the counter-jib to balance a lighter load at farther distances along the longer jib.

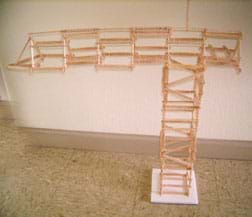

Today we are going to act as a team of engineers working to design a tower crane (see Figure 1 for a student designed-and-built example). Engineers always work within a set of constraints that might be environmental, financial, material, physical and/or time. With these constraints in mind, engineers focus on the design objective: this is what they are trying to accomplish.

In this activity, we will be working within constraints on materials, cost, size and time. You have two main objectives. Your main objective is to design and build a tower crane that remains in static equilibrium while carrying the largest possible load at the largest possible distance along the jib. The second objective is to design your crane such that, with a given weight placed at a given distance along the jib, the deflection of the jib is as small as possible.

These objectives represent real-life issues in designing a tower crane; in order to safely carry a given load, the crane must be structurally sound (with little to no deflection). In addition, to avoid structural failure, the load on the crane must be kept at or below a certain fraction (less than 100%) of the maximum possible load.

(Hand out the worksheets and give students time to complete the second problem on their own.)

Procedure

Before the Activity

- Have a textbook or other weighty object handy for the torque demonstration (as described in the Introduction/Motivation section).

- Prepare a counterweight for the entire class to use. Fill a small paper cup with washers, coins or other small objects. Attach a string by which it can be hung from a finished crane. Measure and record its weight so this value can be used by the students in their design calculations.

- Gather all materials and prepare them for the correct number of teams.

- Make copies of the Static Problems Worksheet, Competition Requirements and Survey.

- Cut a foam core board base for each team.

- Plug in hot glue guns to warm them up.

With the Students

1. (pre-activity assessment) Have students vote on which of three drawings they think are most likely in static equilibrium. (See the Assessment section for details).

2. Conduct the Introduction/Motivation section with the class, which reviews the scientific concepts, works through a practice problem, and presents the engineering design objectives.

3. Divide the class into teams of three to five students each.

4. Hand out the Competition Requirements sheet and explain the competition guidelines. Make sure students understand the two winning requirements: 1) the tower with the greatest load at the greatest distance, and 2) the tower with the least deflection with the specified weight. Use a five-point system, giving the best team in each category a 5, second place a 4, and so on. The team with the highest score from both categories wins. (No team should have more than 10 points.)

5. Have students brainstorm within their groups about how to design their cranes. Give them some ideas: for example, a strong design for the base and mast is a rectangular tower with an "x" frame (truss design).

6. Hand out supplies and tools to each group: a foam core board base, ~150 Popsicle sticks, a hot glue gun and glue sticks.

7. (activity embedded assessment) Once construction is completed, have each group calculate how much weight its crane can hold at the very end of the jib, using the methods learned from the example and worksheet problems (see the Assessment section).

8. Conduct the competition. Since the entire class is sharing a counterweight, make sure the groups are ready to go so that no time is wasted in switching between teams. Once the first part of the competition is completed, write the running total of scores on the board or somewhere handy. When testing for the most weight at the greatest distance, have students start with less weight than the maximum weight that they calculated earlier, working up to the maximum weight. If a team's crane structure breaks or fails structurally, record the last weight achieved. Assign points to winning teams, respectively. Award the overall champion. (Lollipops or candy are good prizes, although a simple round of applause from the rest of the class works, too.)

9. (post-activity assessment) After the competition, lead a class discussion about what went right or wrong. Ask questions such as: "What could you have done to improve your design?" "What design strategies seemed to work best?"

10. Conclude by distributing the Survey for students to complete.

Vocabulary/Definitions

constraint: A restriction on the degree of freedom one has in providing a solution to a problem or challenge.

deflection: The degree to which a structural element is displaced by an applied force.

force: A "push" or "pull" that causes a change in motion.

free-body diagram: A simple diagram that shows all the forces acting on an isolated body.

lever arm: The perpendicular distance from the rotation axis to the force application point.

static equilibrium: A body is in static equilibrium when it is stationary and when the net forces and torques acting on the body are both zero.

torque: The effectiveness of a force acting to rotate a body about an axis.

Assessment

Pre-Activity Assessment

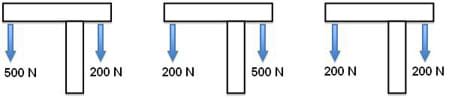

Educated Guessing: Have students vote on which of the three drawings in Figure 5 they think would most likely be in equilibrium. Have them explain their choice in writing. (Correct answer is middle figure.)

Activity Embedded Assessment

Worksheet: After the introduction, students have enough knowledge to complete the Static Problems Worksheet. Work through the first problem with the class; then give students time to complete the second problem on their own. Later, after the cranes are designed and built, have students use the methods presented in the worksheet to calculate the weights that their cranes can hold at several distances.

Post-Activity Assessment

Re-Engineering: Ask students to describe what strategies and designs worked best and what they would change to improve their designs.

Survey: (optional) Hand out the Survey for students to fill out. The survey asks what they learned and where else they see examples of static equilibrium in everyday life.

Safety Issues

- Be aware that glue guns are dangerously hot.

Activity Extensions

Have students create models of their designs in a CAD program (such as AutoDesk Inventor or SolidWorks, if available) and run the stress analysis program to see how their designs hold up.

Activity Scaling

- For lower grades, make the tower dimensions smaller to allow for less room for structural design error. This might include starting with a smaller tower base, and/or using a building material that is smaller than Popsicle sticks (such as toothpicks held together by gumdrops).

- For lower grades, it may be necessary to do all calculations with the students.

- For upper grades, require more in-depth research for truss design and effects of the base in the stability of the tower crane.

- For upper grades, have students more consciously apply the steps of the engineering design process: ask, imagine, plan, create, improve.

Additional Multimedia Support

Learn more about the basic steps of the engineering design process at the Engineering is Elementary website: http://www.mos.org/eie/engineering_design.php

Learn more about the engineering design process at https://www.teachengineering.org/engrdesignprocess.php

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things Teach Engineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!More Curriculum Like This

Learn the basics of the analysis of forces engineers perform at the truss joints to calculate the strength of a truss bridge known as the “method of joints.” Find the tensions and compressions to solve systems of linear equations where the size depends on the number of elements and nodes in the trus...

High school students learn how engineers mathematically design roller coaster paths using the approach that a curved path can be approximated by a sequence of many short inclines. They apply basic calculus and the work-energy theorem for non-conservative forces to quantify the friction along a curve...

References

Bedford, Anthony, and Fowler, Wallace. Engineering Mechanics: Statics, Fifth edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2007.

Wolfson, Richard, and Pasachoff, Jay M. Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Third edition. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1999.

Copyright

© 2010 by Regents of the University of Colorado.Contributors

Stefan Berkower; Nicholas Hanson; Alison PienciakSupporting Program

Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado BoulderAcknowledgements

The contents of these digital library curricula were developed by the Integrated Teaching and Learning Program under National Science Foundation GK-12 grant no. 0338326. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: January 10, 2022

User Comments & Tips