Summary

Students are introduced to ethics and engineering ethics through a short, engaging case study that prompts discussion about how engineers should respond to difficult choices. They explore ethical questions and learn about professional codes of ethics. After researching the code of ethics for an engineering discipline of their choice, students analyze case studies based on real engineering experiences. They identify normative claims and evaluate possible actions using ethical frameworks such as virtue ethics, duty ethics, and utilitarianism. Finally, students complete a case study analysis, applying ethical reasoning to situations from the provided cases or from their own independent research.Engineering Connection

Few high school students are aware of the responsibility that engineers must safeguard public welfare and safety. The benefit of applying this research will be to expose students to these concepts and educate them regarding their future responsibility. If they are taught about it sooner than at the university level, then the odds are greater that the attitudes, skills, and analysis techniques will be assimilated.

Learning Objectives

After this activity students should be able to:

- Define and understand ethics in general and in engineering.

- Practice ethical reasoning through discussion.

- Learn the purpose and structure of professional codes of ethics.

- Apply ethical frameworks to analyze real-world engineering cases.

Educational Standards

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science,

technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN),

a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics;

within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN), a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics; within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards - Science

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

HS-ETS1-2. Design a solution to a complex real-world problem by breaking it down into smaller, more manageable problems that can be solved through engineering. (Grades 9 - 12) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Design a solution to a complex real-world problem, based on scientific knowledge, student-generated sources of evidence, prioritized criteria, and tradeoff considerations. Alignment agreement: | Criteria may need to be broken down into simpler ones that can be approached systematically, and decisions about the priority of certain criteria over others (trade-offs) may be needed. Alignment agreement: | |

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

HS-ETS1-3. Evaluate a solution to a complex real-world problem based on prioritized criteria and trade-offs that account for a range of constraints, including cost, safety, reliability, and aesthetics, as well as possible social, cultural, and environmental impacts. (Grades 9 - 12) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Evaluate a solution to a complex real-world problem, based on scientific knowledge, student-generated sources of evidence, prioritized criteria, and tradeoff considerations. Alignment agreement: | When evaluating solutions it is important to take into account a range of constraints including cost, safety, reliability and aesthetics and to consider social, cultural and environmental impacts. Alignment agreement: | New technologies can have deep impacts on society and the environment, including some that were not anticipated. Analysis of costs and benefits is a critical aspect of decisions about technology. Alignment agreement: |

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association - Technology

-

Apply principles of human-centered design.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Determine the best approach by evaluating the purpose of the design.

(Grades

9 -

12)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Materials List

No additional equipment is required other than a color printer capable of printing two-sided Ethical Twist Cards. Students should have access to the internet for possible research.

Each student needs:

- 1 laptop/tablet with internet access (can be used in pairs)

- 1 Case Studies from Engineering Professionals – Student Guide

- 1 Case Study Analysis Worksheet

For the whole class:

- 1 laptop/tablet with projector to display the Adding an Ethical Twist Presentation

Worksheets and Attachments

Visit [www.teachengineering.org/activities/view/tam-3022-ethical-twist-engineering-design-activity] to print or download.Pre-Req Knowledge

This activity will be most productive for those students who have realized that humans are not governed by their instincts, and that reason may lead us to decide to act contrary to our self-interests.

Introduction/Motivation

Before we start today’s activity, we are going to watch a short video. As you watch, I want you to think about one question: What happens when design decisions go wrong?

(Play the YouTube Short regarding the Ford Pinto (0:52 minutes): https://www.youtube.com/shorts/5ebUJvdYm8A.)

Okay, let’s pause there. First question—no overthinking yet. Do you think the Ford engineers were responsible for this design flaw? (Allow student responses.) Yes, they were responsible.

Next question: What do you think they should have done instead? (Allow student responses. Guide if needed.)

Right. They should have spoken up. They should have stopped production until the flaw could be corrected, even if that meant delays, higher costs, or pressure from management.

Now I want you to notice something. During that discussion, a specific word probably came up again and again. The word “should.” That word matters. When we argue about what someone should do, we are stepping into a bigger way of thinking. That brings us to a few important ideas.

Let’s define a few terms. What is philosophy? (Let students offer answers.) Philosophy is the study of what one should do. What is psychology? (Let students offer answers.) Psychology is the study of what people do.

And now the big one for today: What are ethics? (Let students offer answers.) You might say things like “doing the right thing” or “making good choices.” Those are good instincts. More precisely, ethics is the study of what a person should do, should seek, and should become.

Now let’s connect this to engineering. Engineers make decisions throughout their careers that can affect a lot of people—sometimes millions of people. So, here is a question for you: When engineers are designing something or solving a problem, who do they need to consider? (Potential answers: themselves, their boss or team, their company, the customer, the end user.)

Let’s push this one step further. What about everyone else? What about the rest of the population? This is where ethics becomes critical. Professional engineers follow a code of ethics from the National Society of Professional Engineers. One key principle says engineers must “hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public.”

Let’s unpack that. What do you think “hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public” means? (Allow discussion. Gently guide.) This does not just mean protecting yourself, your job, or your company. It means thinking about your community, your environment, and people you may never meet but who could still be affected by your decisions.

Understanding this kind of responsibility takes practice. One of the best ways to learn is by looking at real-world case studies, stories where people had to make difficult choices.

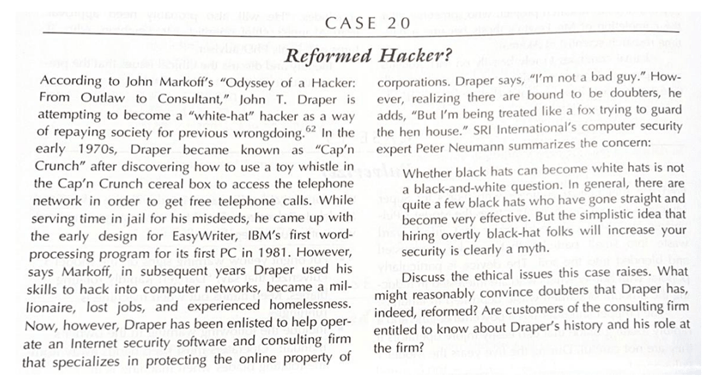

Let’s examine a short ethics case study. It is brief, but it raises big questions. (Read aloud Figure 1 or have students read.)

In this case, the person involved—sometimes called the “Black Hat”—raises several ethical concerns. For example:

- They failed to show good judgment and self-control (virtue ethics).

- They ignored their duty to respect others and follow rules that should apply to everyone (duty ethics).

- Their actions mainly served themselves, not the greater good (utilitarianism).

Here is the dilemma I want you to think about: Is it ever okay to violate someone’s rights or privacy if you believe it helps the common good? (Let students offer answers.) There is no easy answer—and that is the point. Ethics is not about memorizing rules: It’s about learning how to think carefully, responsibly, and courageously when the stakes are high. And as future engineers, scientists, designers, or decision-makers, those questions may one day be yours to answer.

Procedure

Background

Engineering ethics focuses on how engineers ought to act when their decisions affect people, safety, and society. Ethical dilemmas often involve tradeoffs (e.g., safety versus cost, speed versus thorough testing, or loyalty to an employer versus responsibility to the public.) The goal of this activity is not to assign blame or arrive at a single “right” answer, but to help students practice ethical reasoning and justification.

Descriptive claims explain what is happening, while normative claims address what should happen. Because ethics deals with ideals, obligations, and responsibilities, students will frequently use “should” language when analyzing cases. Helping students recognize and articulate these normative claims is a key part of the learning process.

Virtue ethics focuses on character and moral habits such as prudence, integrity, and responsibility. Duty ethics emphasizes obligations, rules, and respect for the autonomy of others. Utilitarianism centers on consequences, asking which action leads to the greatest overall good for the greatest number of people. Students are not expected to master these frameworks, but you should use them as tools to help students organize and justify their reasoning.

Professional Codes of Ethics are formal guidelines created by professional organizations, such as the American Society of Mechanical Engineers or the National Society of Professional Engineers, which outline expectations for professional conduct. Although these codes are not laws, they strongly influence professional accountability and decision-making. A central principle across engineering codes is the obligation to “hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public,” which serves as a foundation for many ethical discussions in this activity.

Case studies are used throughout the activity to reflect the ambiguity of real-world engineering decisions. You should expect multiple reasonable responses, disagreement among students, and evolving opinions as discussions unfold. Your role is to probe student thinking, ask clarifying questions, and encourage justification of decisions rather than declaring answers right or wrong. Socratic dialogue—asking open-ended questions and allowing students time to think—is more effective than lecturing or note-taking for this topic.

When applying ethics to future design challenges using Ethical Twist Cards, recognize that ethical constraints often emerge after a design process has already begun. The twists simulate real engineering considerations such as accessibility, environmental impact, sustainability, and equity. These twists are intended to prompt iteration and reflection rather than complete redesigns. Students should be encouraged to think about how ethical considerations affect end users, communities, and the environment.

Before the Activity

- Review the concepts described in the Adding an Ethical Twist Presentation.

- As these discussions are most appropriately addressed in the form of a Socratic dialogue, review resources on conducting these types of discussions if it is new for the students.

- Some classes may run with the idea of discussion, but in the event class discussion falls flat, have students respond on paper then share their ideas.

- Review the Case Studies from Engineering Professionals – Teacher Guide.

- Make copies of the Case Studies from Engineering Professionals – Student Guide. (1 per pair or student)

- Make copies of the Case Study Analysis Worksheet. (1 per student)

During the Activity

Day 1: Introduction to Ethics and Engineering Ethics

- Introduce the activity by reading the Introduction and Motivation section, which includes a short case study. (Note: The provided case study can be used to engage the students; however, you are encouraged to find a case study that is timely and fits your students.)

- Go through the Adding an Ethical Twist Presentation with the students. Note: The author finds that Socratic dialogue is more effective than notes.

- Introduce professional codes of ethics: Codes of ethics are formal guidelines created by professional organizations that outline the values, responsibilities, and standards of behavior expected of people working in a specific field. They describe how professionals should act, what they should prioritize, and how they should make decisions, especially when facing difficult or high-stakes situations.

- Give students time to research the code of ethics for an engineering discipline of their choice (e.g., mechanical engineering’s ASME Code of Ethics.) See the Code of Ethics for Professional Engineers Links for suggested links.

Day 2: Case Study Analysis

- Distribute one Case Studies from Engineering Professionals – Student Guide to each student.

- Have students read the case studies.

- Optional Show students how to break down a case. For example:

- Summarize the case study: [Referencing the first highlighted case study] Ms. B is an aerospace engineer working for NASA and was overseeing two companies; one company was not testing enough or being very safe for a program dealing with visiting crews.

- Is this involving a normative claim? Normative claims are the claims regarding what is ideal. They are not simply opinions or descriptive claims. (Answer: Yes.)

- What would you do, and why? (Answer: Answers will vary. The best ethical decision seems to be that the unsafe company should be removed or made to increase their testing to reach safe levels for the astronauts involved. Above all, do not sanction these shortcuts. Why: Virtue ethics says you should strive to reach potential and use prudence to determine the proper end to pursue. Duty ethics says you should have respect for the rationality and autonomy of other people. Utilitarianism says you should do something if and only if there is no other act that leads to better consequences for all involved.)

- Provide the Case Study Analysis Worksheet to each student.

- Have students answer the Case Study Analysis Worksheet either individually or in small groups from their own encounters, problems they found on the internet, or the cases mentioned the Case Studies from Engineering Professionals – Student Guide.

Applying Ethics to Future Design Days

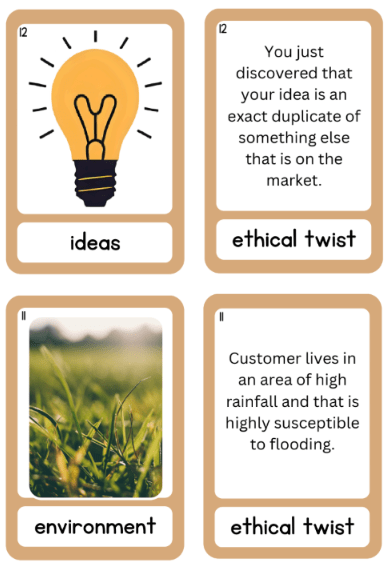

During a future engineering design challenge, introduce the Ethical Twist Cards after students have begun the engineering design process. The “Ethical Twist Cards” are similar to how “twists” are introduced to competing chefs in baking shows when their creations are under way. The Ethical Twist cards are double-sided set of 12 cards. Each has an ethical issue or additional design constraint.

Students can read the topics prior to selecting a card, or the “twist” can be random. The “twists” are things like:

- Your customer is wheelchair bound.

- Your design must also aesthetically brighten up an aging and poorly maintained part of town.

- Your design must allow a third-world peasant farmer to do a task alone that used to take two or more people to do.

- Your customer lives in an environmentally sensitive desert area in the Southwest, and your design must include features that show minimal impact on the land, wolves, prey animals, ranchers, and residents.

- Your customer is in an impoverished area and needs the complicated components of your machine to be simplified so that they can be easily maintained and repaired with hand tools.

- Certain parts must be replaced with a more sustainable alternative.

Students from each group will pick a card when they start building their design challenges through the year.

The “twist” challenge requires groups to quickly iterate to accommodate, but none of the twists should cause a complete redesign. This additional step provides an opportunity for students to consider the end user, environment, or community.

In the design project deliverables, have students define their ethical twist and reflect on how their twist changed their design. After implementing an ethical twist in their design, students should address their solutions in their project design. The project deliverables should include reflection questions: (1) Describe the ethical dilemma you had to address. (2) What ethical issues and/or theories did you invoke to analyze the main issues? (3) How did you choose to address these concerns in your design? (4) Can you think of a better or more comprehensive approach to address the issue? Example responses: Student Responses to the Ethical Twist.

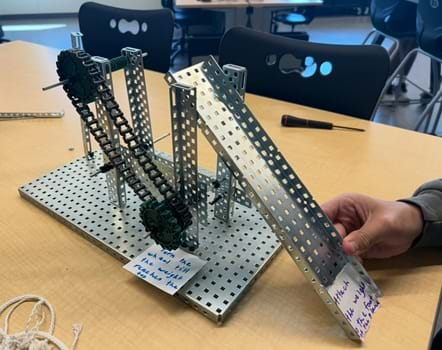

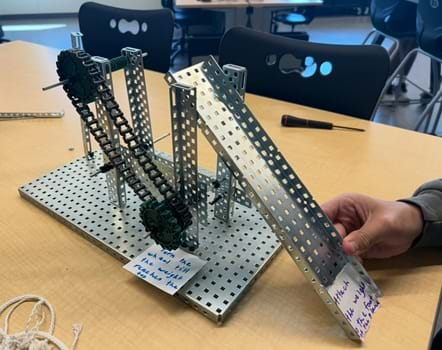

For example, in Student Design #1, students replaced three steel pieces with cardboard and cardstock materials to give their design a lower carbon footprint as shown here:

In Student Design #2, students were required to adapt their design for an end user who is vision impaired. Their final design included high-contrast signage and Braille plates at user input as shown here:

Vocabulary/Definitions

autonomy: Free and informed consent.

beneficence: Doing something good.

case study: A story of something that happened where details are given and the reader can analyze and decide what they would do.

courage: Having the right response to fear.

descriptive claim: Claims regarding facts: What I See. What I do. These ARE NOT ethical elements.

duty ethics: (Kant) Having respect for the rationality and autonomy of other people and not carving out exceptions for oneself.

ethics: The study of what a person should do, should seek, and should become.

fundamental ethical theories: Virtue ethics, duty ethics, and utilitarianism.

justice: Giving each person their due.

justice: People who take on risks should also be the beneficiaries.

mid-level principles : General guidelines that act as a bridge between fundamental ethical theories and specific moral rules. Beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice.

nonmaleficence: Not causing harm.

normative claim: Claims regarding what is ideal: What should I do? These ARE ethical elements.

opinion: Something someone says or believes is true, but that cannot be debated; “Mario Kart is the best video game.” These ARE NOT ethical elements.

philosophy: The study of what one should do.

prudence: Practical judgment. Determining the proper end to pursue and best means to achieve it.

psychology: The study of what one does.

temperance: Having the right response to the desire to acquire something.

utilitarianism: (Bentham/Mill) An act is morally right if and only if there is no other act that leads to better consequences for everyone affected by the act. Cost-benefit analysis.

virtue ethics: (Aristotle) Striving to determine and achieve “the good life,” where potential is actualized and virtues are developed. See cardinal virtues prudence, temperance, courage, and justice.

Assessment

Pre-Activity Assessment

Discussion Questions: During the Introduction and Motivation section, students are asked the following questions to help assess their pre-activity knowledge:

- What is philosophy? (Answer: The study of what one should do.)

- What is psychology? (Answer: The study of what one does.)

- What are ethics? (Possible answers: Doing what is right, doing the right thing, etc. Answer: Ethics is the study of what a person should do, should seek, and should become.)

- Engineers make many decisions through their careers that impact many people in society. Who do they need to consider when making a design or solving a problem? (Answer: Themselves, their boss/team, their company, customer, end users.)

- What about the rest of the population? (Answer: There are many layers of thought and reflection that are required to “hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public.” -National Society of Professional Engineers Code.)

- What does “hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public” mean to you? (Answer: Answers vary. Guide students past the idea of providing for welfare of themselves/their company/customer to include their community and environment. To begin to understand the concepts and logic required, we can examine case studies.)

Activity Embedded (Formative) Assessment

Monitoring and Prompts: As students work on the Case Study Analysis Worksheet, the teacher circulates around the room and asks students to clarify their thinking about the ethics of various case studies. Sample questions include:

- How would you summarize this case study?

- Who is affected by the situation?

- What do you propose should happen, and why?

Post-Activity (Summative) Assessment

Case Study Analysis Worksheet: Students use short summaries from their own encounters, problems they found on the internet, or cases mentioned in the Case Studies from Engineering Professionals – Student Guide to apply their knowledge of ethics.

Troubleshooting Tips

If students have trouble making an argument, work through additional examples with them. You can always fall back to “cause no harm.”

Activity Extensions

Engineering Ethics in the Real World:

- Have students find someone doing a job they are interested in and interview them before the activity. Have students use the Interview Questions.

- After the interviews take place, have students deliver presentations on their interviewees.

- While they are presenting, write down all of the ethics issues that were described by their interviewees.

- In a later class, choose two or three of the noted interviewee ethic issues and discuss as a class.

- Work as a class through how to break these issues down and articulate the questions.

Activity Scaling

For lower grades or students new to ethics:

- Use one teacher-selected case study instead of multiple case studies.

- Introduce only one ethical framework (e.g., “doing the most good” or “keeping people safe”) without formal terminology.

- Provide a guided worksheet with sentence starters instead of open-ended prompts.

- Replace independent research with a teacher-provided code of ethics excerpt.

- Complete the Case Study Analysis Worksheet as a think–pair–share activity rather than a full written assignment.

For higher grades or more advanced learners:

- Assign multiple case studies and have students compare ethical conflicts across cases.

- Require students to explicitly reference ethical frameworks when justifying decisions.

- Have students research and present codes of ethics from different engineering disciplines.

- Introduce conflicting constraints (e.g., safety vs. cost vs. schedule) and require students to prioritize.

- Use student-led facilitation of case discussions.

- Connect ethical reasoning directly to future engineering design projects using the Ethical Twist Cards.

Additional Multimedia Support

Links in the Code of Ethics from Professional Engineers Links.

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things Teach Engineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!References

Harris et al. 2019. Engineering Ethics: Concepts and Cases. 6th edition. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Miller, Glen. 2018. “Aiming Professional Ethics Courses Toward Identity Development.” In Englehardt and Pritchard (eds.) Ethics Across the Curriculum—Pedagogical Perspectives, 89-105. Cham: Springer.

Miller et al. 2023. Editors’ Introduction to Thinking Through Science and Technology: Philosophy, Religion, and Technology in an Engineered World, 1-10. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Whitbeck, Caroline. 1996. “Ethics as Design: Doing Justice to Moral Problems.” Hastings Center Report 26, no. 3: 9-16.

Catalano, G. D. 2014. Engineering ethics: Peace, Justice, and the Earth, second edition. Springer International Publishing.

Ethical Twist Cards and images created with Canva stock images and AI prompted by Forrest Medcalf. Text is original by Forrest Medcalf.

Copyright

© 2026 by Regents of the University of Colorado; original © 2025 Texas A & M UniversityContributors

Forrest Medcalf, Author; Morgan Williamson, Program Administrator; Luis Rivera, Master Teacher; Dr. Glen Miller, Dr. Bimal Nepal, Dr. Michael Johnson, and Dr. Amarnath Banerjee, MentorsSupporting Program

Research Experience for Teachers (RET) E3 Program by Texas A&M UniversityAcknowledgements

This curriculum was developed under National Science Foundation RET Grant #2134465. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Last modified: February 12, 2026

User Comments & Tips