Quick Look

Grade Level: 4 (3-5)

Time Required: 45 minutes

Expendable Cost/Group: US $4.50

Group Size: 4

Activity Dependency: None

Associated Informal Learning Activity: Will It Conduct?

Subject Areas: Algebra, Physical Science

NGSS Performance Expectations:

| 5-PS1-3 |

Summary

By engaging in the science and engineering practice of making observations and measurements to produce data, students make sense of the phenomenon of electricity. Applying the disciplinary core idea of measurement, students build their own simple conductivity tester and explore whether given solid materials and solutions of liquid are good conductors of electricity. While exploring the phenomenon of electricity, students also apply the crosscutting concept of standard units.

Engineering Connection

Electrical and computer engineers design circuit boards that serve as the "brains" of the computers, toys, cars, planes and appliances we use every day. Engineers are well versed in which materials and solutions are the best conductors and insulators, and when designing, they match a material's properties and characteristics to the situation. Through the appropriate selection of materials for microchips and parts, engineers design devices and appliances that we rely upon every day.

Learning Objectives

After this activity, students should be able to:

- Predict whether an object is likely to conduct electricity.

- Construct a conductivity tester to determine whether their prediction was correct.

- Compare and order objects and materials based on their relative ability to conduct electricity.

- Understand that engineers must appropriately select materials for microchips and parts in order to design devices and appliances that we rely upon every day

Educational Standards

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science,

technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN),

a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics;

within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN), a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics; within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards - Science

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

5-PS1-3. Make observations and measurements to identify materials based on their properties. (Grade 5) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Make observations and measurements to produce data to serve as the basis for evidence for an explanation of a phenomenon. Alignment agreement: | Measurements of a variety of properties can be used to identify materials. (Boundary: At this grade level, mass and weight are not distinguished, and no attempt is made to define the unseen particles or explain the atomic-scale mechanism of evaporation and condensation.) Alignment agreement: | Standard units are used to measure and describe physical quantities such as weight, time, temperature, and volume. Alignment agreement: |

Common Core State Standards - Math

-

Draw a scaled picture graph and a scaled bar graph to represent a data set with several categories. Solve one- and two-step "how many more" and "how many less" problems using information presented in scaled bar graphs.

(Grade

3)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Represent and interpret data.

(Grade

4)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use place value understanding to round decimals to any place.

(Grade

5)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association - Technology

-

The process of experimentation, which is common in science, can also be used to solve technological problems.

(Grades

3 -

5)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

State Standards

Colorado - Math

-

Draw a scaled picture graph and a scaled bar graph to represent a data set with several categories.

(Grade

3)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Represent and interpret data.

(Grade

5)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use place value understanding to round decimals to any place.

(Grade

5)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Colorado - Science

-

Show that electricity in circuits requires a complete loop through which current can pass

(Grade

4)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Materials List

Each group needs:

- 4 wide rubber bands

- 2 or 3 D-cell batteries

- 1 #40 light bulb (available at most hardware stores)

- 1 #40 light bulb holder (available at most hardware stores)

- 2.5 ft (76 cm) insulated wire (gauge AWG 22) (available at most hardware stores)

- 2 in (5 cm) wide strip of aluminum foil (the foil box width should be long enough)

- 4 Will It Conduct? Worksheets

- 4 Elemental Conductivity Math Worksheets (suitable for grades 4 and 5)

For the entire class to share:

- An assortment of solid test objects: Nails or screws (of various metals), glass stirring rod, wooden dowel, cardboard, rubber eraser, rubber shoe sole, plastic utensil, old metal utensil, brass key, cork, copper wire, chalk, aluminum foil, graphite (from a mechanical pencil), plastic pen, feathers, Styrofoam, etc.

- An assortment of test solutions including: Tap water, Saltwater (using distilled water), Sugar water (using distilled water), Baking soda and water (using distilled water), citric acid, vinegar, Gatorade or sports drink

- An assortment of test solutions: Tap water with a few of the following items in three strengths: salt, sugar, baking soda, citric acid, vinegar, ammonia; or Pedialyte drink, Gatorade or sports drink

- Glass beakers or plastic cups for each test solution

- Masking tape

- Distilled water

- Tap water

- Marking pen (for labeling the solutions)

- Wire strippers or sandpaper (to remove insulation at wire ends)

Note: Many of the materials required for this lab can be reused in other electricity activities. When the batteries eventually wear out, dispose of them at a hazardous waste disposal site.

Worksheets and Attachments

Visit [www.teachengineering.org/activities/view/cub_electricity_lesson04_activity1?cs=0&gsc=2&hl=en-US&biw=465&bih=703] to print or download.Introduction/Motivation

Before starting the activity, you may want to remind students that current electricity is the movement of electrons from atom to atom. You may also want to review that electrons carry a negative electric charge.

To begin, ask students if they know where we get electricity from? (Possible answers: The socket in the wall, a power plant, from fossil fuels.) Explain to students that the current electricity we use in schools, businesses and homes comes from a power plant. The power plant sends electricity to substations, which are located in neighborhoods. The substations send the electricity to local businesses and houses.

Next, ask students if they know how current electricity is able to move from a power plant to substations and, finally, to businesses and homes? (Answer: Via electrical wires.) Now, ask students if they know from what material these wires are made? (Answer: Copper.) Show the class a few pennies and explain that the wires that link a power plant, to a substation, and then to businesses and homes are made from copper...just like a penny! Inform students that we use copper for electrical wires because electricity can easily flow through copper. Explain that current electricity can flow more easily through some objects than others. The materials that electrons can move through are called conductors. Most metals make good conductors because the electrons are loosely attached to the atoms. When this is the case, a negative charge buildup can push these electrons through the material. Now, ask students if only solids can conduct electricity? (Answer: No. Electrolyte solutions can also conduct electricity.) Explain that when certain solids are dissolved in a liquid, the resulting solution is able to conduct electricity; we call these solutions electrolyte solutions.

Ask students if they know what we call materials that do not allow electrons to flow through them? (Answer: Insulators.) In an insulator, the electrons are tightly attached to the atoms in a material and cannot be forced to move from one atom to another, so no electricity flows. Some good examples of insulators include plastic, cloth, air, rock and glass. Explain that they will learn more about conductors and insulators during the activity.

Finally, share with students that electrical engineers also use copper wires as conductors of electricity when they design electronic circuit boards (see Figure 1). The copper wires on a circuit board are called traces and are fixed on an insulated plastic board (many times green in color) called a substrate. The copper traces are carefully mapped on a circuit board by electrical engineers connecting electrical components (such as resistors, capacitors and microchips) on the circuit board and providing electricity to these components.

Procedure

Background — Solids

Metals are good conductors. Plastics, wood products, ceramics and glass are insulators. The graphite from a pencil conducts, but has a higher resistance than the metals. Graphite, like silicon, is a semiconductor; it has electrical properties intermediate between insulators and conductors. So, in the activity, depending on the length of the graphite, the light bulb may be considerably dimmer than when a metal object is used.

The resistance of an object depends not only on its composition, but its length, cross-sectional area and temperature. For example, a long piece of copper has a higher resistance than a short piece of copper of the same diameter. A piece of copper 1 m long with a diameter of 2 cm has a higher resistance than a piece of copper 1 m long with a diameter of 3 cm. If the temperature of a piece of copper is raised, its resistance also increases.

Engineers determine the most efficient means of utilizing materials for a given purpose. When an engineer designs an object with a particular resistance, they must consider how expensive the material is, how the shape of the object will affect its resistance, and to what temperature ranges it will be exposed. For example, an engineer may use a more expensive material to make a small, critical circuit element, and a cheaper material to make larger circuit elements.

Background — Liquids and Solutions

It is the presence of ions in a solution that enables it to conduct electricity. Positive ions move to the negative electrode and negative ions move to the positive electrode. The conductivity of a solution is proportional to the concentration of ions in the solution. Therefore, solutions with low concentration of ions only weakly conduct electricity; in cases like this, in the activity, the bulb of the conductivity tester may not light up or may glow dimly.

The light bulb will not light up when the electrodes are placed in distilled water. There may, however, be a very small current in the circuit due to the presence of H+ (hydrogen ions) and OH- (hydroxide) ions in the water. These ions are produced when water molecules spontaneously dissociate. These ions also recombine spontaneously to form water molecules. Because only a few water molecules dissociate in a given time, the ions make up a very small proportion of the particles in the distilled water. Therefore, distilled water is a very poor conductor. Tap water, on the other hand, can be a good electrical conductor due to the presence of many different ions such as Ca2+, Na+, Li+, Cl-, etc. However, at the low voltages used in this activity, tap water might not conduct electricity.

Adding an ionic solid, or salt, to distilled water produces a solution that conducts electricity. When an ionic solid such as table salt, NaCl, is added to water, it dissociates — breaks apart into oppositely-charged ions — into Na+ and Cl-. Salts are strong electrolytes — they dissociate completely. Increasing the amount of salt in a solution increases the conductivity of the solution.

Acids and bases also break down to form ions when dissolved in water. Therefore, a solution of an acid or a base conducts electricity. Strong acids, such as sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid, and strong bases, such as sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide, are strong electrolytes because when they dissolve in water, almost every molecule dissociates to produce ions. On the other hand, weak electrolytes, such as weak acids and weak bases, produce relatively few ions when dissolved in water. Citric acid and acetic acid (in vinegar) are weak acids. Baking soda and ammonia are weak bases. When weak electrolytes dissolve in water, the solution is a poor conductor. Increasing the concentration of a weak electrolyte in a solution increases the conductivity of the solution. Increasing the amount of acid or base in a solution increases the conductivity of the solution, allowing charge to move through the circuit and light the bulb.

Materials that dissolve in water without producing any ions are nonelectrolytes. Sugar, ethanol, and kerosene are non-electrolytes. Non-electrolytes produce solutions that do not conduct electricity when dissolved in water.

Before the Activity

- Collect an assortment of solid objects for the students to test as conductors or insulators (see Materials List for examples).

- Make the solutions for the students to test. Mix distilled water and one tablespoon (14.8 mL) of one of the suggested ingredients (X) (salt, sugar, baking soda, citric acid, vinegar or ammonia) in different labeled containers.

- Put one cup of distilled water in a container and label it. Put one cup of tap water in another cup and label it. Put one cup of sports drink in a cup and label it.

- Cut four 3 in (7.6 cm) pieces of wire and two 9 in (23 cm) pieces of wire for each team.

- Print worksheets (Will It Conduct? Worksheet and Elemental Conductivity Worksheet), one per student.

With the Students

- Using wire strippers or sandpaper, strip 1/2 in (1.3 cm) of insulation from the ends of each piece of wire to ensure a good connection.

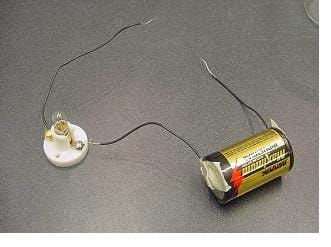

- Tape one end of a short piece of wire to the positive terminal of a D-cell battery using masking tape. Connect the other end of the short wire to one terminal of the light bulb holder. To make a good connection, wrap the wire around the screw on the bulb holder terminal in a U-shape. Connect a long piece of wire to the negative terminal of the D-cell battery using masking tape. Connect a second piece of long piece of wire to the open terminal of the bulb holder.

- Test your circuit by touching the free ends of wire together. What happens? (Answer: The circuit is complete and the bulb lights.) If the bulb does not light, check all connections and try again. Now, leave the circuit open. We will use this circuit as a conductivity tester.

- Use the circuit as a conductivity tester for solid objects. Get materials from your teacher to test. Predict whether each item will conduct electricity. Then, touch the two wire ends to a test object to see if the circuit is completed. How will you know if an item is a conductor or an insulator? (Answer: If an object is a conductor, the bulb will light. If an object is an insulator, the bulb will not light.)

- Predict which objects you think will conduct electricity. Record your predictions on the Will It Conduct? Worksheet.

- Use the circuit tester to determine whether each object is a conductor or an insulator. Record your test results on the worksheet.

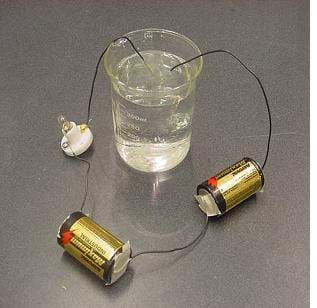

- Make a conductivity tester for liquids: Modify the conductivity tester by adding one or two more batteries in series (see Figure 3). Use short pieces of wire to connect the batteries in series.

- Carefully wrap aluminum foil around the end of the two open-ended wires to make an electrode. (Note: No foil shown in Figure 3 setup.) Make each electrode 1 in (2.5 cm) long by ¼ in (6 mm) wide.

- Test your circuit. Touch the pieces of a foil together to close the circuit. What happens? (Answer: When you touch the foil electrodes together the bulb lights because the circuit is complete.)

- Predict which liquids will conduct electricity, recording your predictions on the worksheet. How will you know whether a liquid conducts electricity? (Answer: If a liquid conducts electricity, the bulb will light.)

- Use the circuit as a conductivity tester for liquids. Test each liquid by submerging the electrodes in the solution and holding the electrodes close without touching each other. Be careful to only hold the wire where it is insulated. Put on new aluminum foil electrode strips for each test.

- Record your test results on the worksheet. How were your results different from your predictions?

- Complete any remaining questions on the Will It Conduct? Worksheet.

- Complete the Elemental Conductivity Math Worksheet.

Assessment

Pre-Activity Assessment

Discussion Question: Solicit, integrate and summarize student responses:

- Ask students if only solids can conduct electricity? (Answer: No. An electrolyte solution can also conduct electricity.)

Prediction: Have students predict the outcome of the activity before the activity is performed.

- Place a penny, a glass of tap water and a piece of paper on the table, and ask students to predict which will conduct electricity the best and worst. (Answer: Only the penny will conduct electricity well.)

Activity Embedded Assessment

Worksheet: During the activity, have students use the Will It Conduct? Worksheet to record their observations and answer questions.

Post-Activity Assessment

Prediction Analysis: Have students compare their initial predictions with their test results, as recorded on the worksheets. Ask the students to explain why some solutions conducted electricity while others did not.

Inside-Outside Circle: Have the students form into two concentric circles (an inner-outer circle), so that each student has a partner facing them from the other circle. The outside circle faces in and the inside circle faces out. Three people may work together if necessary. Ask the students a question (see below). Have partners consult each other to discuss the answer. If they cannot agree on an answer, they can consult with another pair. Call for responses from the inside or outside circle or the class as a whole. Repeat until all the questions have been answered correctly. Questions:

- Why do engineers use conducting materials in circuits? (Answer: Engineers use conductors to make the parts of a circuit that will have electric current in them.)

- An engineer has to choose between making wire from copper or silver. Which material do you recommend they choose? Why? (Answer: Copper is cheaper than silver.)

- What types of materials are good conductors? (Answer: Any metals.)

- Do some metals conduct better than others? Why? (Answer: Yes, conductance varies with the number of valence electrons (those in the outer shell, available to move around). For practical applications, density plays an important role, and that's why power lines are usually made of aluminum instead of copper (less conductive material, but much lighter, so even if thicker, aluminum will be lighter for the same conductance.)

- How will you know whether a liquid conducts electricity? (Answer: If the liquid conducts electricity, the circuit becomes closed and the light bulb lights up.)

- What were the three best conductors in the activity? (Answer: Will vary, depending on materials provided.)

- What was the best solid conductor in the activity? (Answer: Will vary.)

- What was the best liquid conductor in the activity? (Answer: Will vary.)

Safety Issues

- Ask students to be especially careful when stripping the wire, so they do not cut themselves or other students.

- Ask students to avoid holding the insulated wire on the D-cell battery with their fingers for extended periods of time because the stripped ends of the wire heat up when held on the battery terminals.

Troubleshooting Tips

Remind students to be sure to replace the aluminum foil electrodes each time they test a different solution because the electrodes may become contaminated with the previous solution.

Students should be careful to hold the foil electrodes slightly apart when placed in a liquid; they will get a false positive if the two electrodes touch.

Activity Extensions

Choose one conducting material to test with the conductivity tester. Obtain samples of the material having different lengths and cross-sectional areas. Challenge students to use their conductivity tester to show that resistance increases with increasing length and decreases with increasing cross-sectional area.

Have student's research acids and bases. What are some common acids and bases, and how are they used?

Have students conduct research on the use of different materials in electric circuits: copper, gold, aluminum, paper, plastic, etc.

Activity Scaling

- For lower grades, have students gauge conductivity by the brightness of the bulb. They should place each object in a category according to the intensity of light produced by the bulb when they tested the object: bright, dim, nothing.

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things Teach Engineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!More Curriculum Like This

Students gain an understanding of the difference between electrical conductors and insulators, and experience recognizing a conductor by its material properties. In a hands-on activity, students build a conductivity tester to determine whether different objects are conductors or insulators.

Students are introduced to the concept of electricity by identifying it as an unseen, but pervasive and important presence in their lives. They compare conductors and insulators based on their capabilities for electron flow. Then water and electrical systems are compared as an analogy to electrical ...

Students learn about current electricity and necessary conditions for the existence of an electric current. Students construct a simple electric circuit and a galvanic cell to help them understand voltage, current and resistance.

Student groups make simple conductivity testers each using a battery and light bulb. They learn the difference between conductors and insulators of electrical energy as they test a variety of materials for their ability to conduct electricity.

References

Experiments in Electrochemistry, Fun Science Gallery, accessed March 2004. Formerly available at: http://www.funsci.com/fun3_en/electro/electro.htm

Where Electricity Comes From, Southern California Edison, accessed March 2004: http://www.sce.com/

Visualizing Electron Orbitals, Georgia State University, accessed August 2013: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/chemical/eleorb.html

Copyright

© 2004 by Regents of the University of Colorado.Contributors

Xochitl Zamora Thompson; Sabre Duren; Joe Friedrichsen; Daria Kotys-Schwartz; Malinda Schaefer Zarske; Denise CarlsonSupporting Program

Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado BoulderAcknowledgements

The contents of this digital library curriculum were developed under a grant from the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), U.S. Department of Education and National Science Foundation GK-12 grant no. 0338326. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department of Education or National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: May 14, 2021

User Comments & Tips