Quick Look

Grade Level: 6 (4-6)

Time Required: 1 hours 45 minutes

(two 50-minute sessions)

Expendable Cost/Group: US $0.00

Group Size: 1

Activity Dependency: None

Subject Areas: Chemistry

NGSS Performance Expectations:

| 5-ESS3-1 |

Summary

The goal of this activity is for students to learn how to tell a story in order to make a complex topic (such as global warming) easier for a reader to grasp. Students study how narratives in scientific and technical writing can help readers gain a better understanding of human motivation, as well as the "science" of imagination. Finally, students recognize why the ability to communicate and understand science is almost as important as developing the science itself.Engineering Connection

When scientists and engineers report their findings, they are in essence telling a story. To make complex topics such as global warming or pollution easier for an audience or reader to understand, engineers often relay real-life stories that describe how these situations impact the lives of people. In this way, they are more successful in getting others to understand their point of view and their message.

Learning Objectives

After this activity, students should be able to:

- Learn how to tell a story in order to make a complex topic (such as global warming) easier for a reader to grasp,

- Incorporate source materials into their speaking and writing (for example, interviews, news articles, encyclopedia information),

- Write and speak in the content areas using the technical vocabulary of the subject accurately,

- Read, respond to and discuss literature that represents points-of-view from places, people, and events that are familiar and unfamiliar.

Educational Standards

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science,

technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN),

a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics;

within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN), a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics; within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards - Science

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

5-ESS3-1. Obtain and combine information about ways individual communities use science ideas to protect the Earth's resources and environment. (Grade 5) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Obtain and combine information from books and/or other reliable media to explain phenomena or solutions to a design problem. Alignment agreement: | Human activities in agriculture, industry, and everyday life have had major effects on the land, vegetation, streams, ocean, air, and even outer space. But individuals and communities are doing things to help protect Earth's resources and environments. Alignment agreement: | A system can be described in terms of its components and their interactions. Alignment agreement: Science findings are limited to questions that can be answered with empirical evidence.Alignment agreement: |

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association - Technology

-

Analyze how different technological systems often interact with economic, environmental, and social systems.

(Grades

6 -

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Examine the ways that technology can have both positive and negative effects at the same time.

(Grades

6 -

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

State Standards

Colorado - Science

-

Interpret and analyze data about changes in environmental conditions – such as climate change – and populations that support a claim describing why a specific population might be increasing or decreasing

(Grade

6)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Materials List

Paper and pencils

Pre-Req Knowledge

A familiarity with the Earth's ozone layer, global warming, air pollution and other environmental case studies.

Introduction/Motivation

Have you ever noticed how a story seems to draw you into the world it creates? Have you ever felt as though the world of the story was so real that it seemed you were living the events along with the characters? That ability to capture your imagination is something writers of non-fiction make use of as well. When writing accounts of wild fires, news reporters do not just report the facts — how many acres were burned, how many firefighters battled the fire, how many homes were lost — they include stories of the people who lost their homes and stories of the heroism of the firefighters. Telling a story can be an engaging way to begin an essay or report because our audience wants to hear more.

Procedure

Global warming and expansion of the ozone hole are subjects about change. These topics are disturbing because human beings prefer stability. One way people deal with fear of change is to tell stories that help make the unfamiliar, familiar.

In a sense, all myths are about change: how things come into being, grow, change form and die. From ancient times, storytelling has been a means not only to entertain, but also to convey significant cultural information about how and why change takes place. At a deep level, stories help us understand how the world works.

When scientists and engineers report their findings, they are in essence telling a story, "recounting" their results. When journalists, or scientists writing for a popular audience, seek to engage the reader, they frequently begin their reports with a story. Scan any newspaper or magazine; most feature articles start with a story.

This technique has the twofold advantage of providing both an emotional and a rational appeal: the story speaks to the reader's capacity for empathy while providing a specific case from which logical conclusions can be inferred. In this respect it is a miniature case study.

Students were introduced to case studies in the Is That Legal? A Case of Acid Rain literacy activity. The current activity further develops the concept that storytelling can be also used effectively in writing intended to explain a technical topic.

Encourage students to develop storytelling skills for use in non-fictional expository writing. Telling a story is a convenient way to introduce a topic. The story engages the writer's imagination, as well as the reader's, and makes the rest of the essay or report easier to write. The problem of the blank page is solved.

In addition, non-fiction storytelling is good preparation for the challenge of telling a fictional "made up" story. In a non-fiction story, the elements of the storyline come ready-made. Students can then focus on organizing the story and developing their storytelling technique in order to relate the tale with maximum impact. Those skills can be transferred to fictional storytelling.

Observing

As examples of this writing technique, read aloud to the class the following brief stories. Mutant Frogs and Meltdown in the North are the introductions to articles on environmental pollution and global warming published in Scientific American magazine. After reading, ask the students: Do the stories make you want to read more?

Mutant Frogs

One hot summer day in 1995 eight middle school children planning a simple study of wetland ecology began collecting leopard frogs from a small pond near Henderson, Minn. To their astonishment, one captured frog after another had five or more hind legs, some twisted in macabre contortions. Of the 22 animals they caught that day, half were severely deformed. A follow-up search by pollution-control officials added to the gruesome inventory. Occasional frogs in the pond had no hind limbs at all or had mere nubbins where legs should be; others had one or two legs sprouting from the stomach. A few lacked an eye...

Source: Blaustein, Andrew R., and Pieter T. J. Johnson. "Explaining Frog Deformities." Scientific American 288, no. 2 (2003): 60-65. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26060165.

The article goes on to explain the interrelated reasons why the frogs became deformed: ultraviolet radiation owing to thinning of the protective ozone layer of the planet by chemical pollutants in the atmosphere; chemical pollutants in pond water; parasites that frogs were vulnerable to because they were weakened by the other factors.

Meltdown in the North

Snow crystals sting my face and coat my beard and the ruff of my parka. As the wind rises, it becomes difficult to see my five companions through the blowing snow. We are 500 miles into a 750-mile snowmobile trip across Arctic Alaska. We have come, in the late winter of 2002, to measure the thickness of the snow cover and estimate its insulating capacity, an important factor in maintaining the thermal balance of the permafrost. I have called a momentary halt to decide what to do. The rising wind, combined with -30 degree Fahrenheit temperatures, makes it clear we need to find shelter, and fast. I put my face against the hood of my nearest companion and shout: "Make sure everyone stays close together. We have to get off this exposed ridge."

Source: Sturm, M., Perovich, D., & Serreze, M. (2003). Meltdown in the North. Scientific American, 289(4), 60-67. Retrieved September 6, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26060487

The author comments that he and his companions might freeze to death while looking for evidence of global warming. As he lists the changes taking place in the Arctic — "the warmest air temperatures in four centuries, a shrinking sea-ice cover, a record amount of melting on the Greenland ice sheet, Alaskan glaciers retreating at unprecedented rates," and more... — it becomes clear that the Arctic is undergoing a profound transformation. (The author's comment about freezing to death in the search for evidence of global warming is an example of using irony as a literary device.)

Thinking

Now let's analyze the introductory stories in terms of how they are developed and organized. First, notice that both stories answer most of the "journalist's questions" — who, what, when, where, how, why — in just one paragraph. The "Mutant Frogs" paragraph covers the questions in the first sentence: One hot summer day in 1995 [when] eight middle school children [who] planning a simple study of wetland ecology [what] began collecting leopard frogs from a small pond [how] near Henderson, Minnesota. [where].

"To their astonishment" is a phrase that creates a moment of suspense and turns the story in a grim direction. As it turns out, the "simple" study of wetland ecology is about to gain international attention. The additional details make you want an answer to the big "why." Why are the frogs so deformed?

The "Meltdown in the North" paragraph also answers the journalist's questions, but creates its air of mystery by not directly telling you who "we" are (although you can assume "we" are scientists). It is written from first-person point-of-view and focuses not on "who" but on "what" — environmental details. This treatment supports the author's argument in the body of the article that the environment of the Arctic is in fact changing.

Writing

Imagine you are changing the presentation you prepared in the Is That Legal? A Case of Acid Rain literacy activity, into an article, and you want to start with the human-interest story you included in the presentation. Or, think of another topic that interests you and highlight a brief story to illustrate the main point you wish to make. A third option is to start with a story and develop the article from the story as a way to explain what happened.

Consider modeling your paragraph after the style and structure of one of the two paragraphs we have just analyzed. (See Writing Stories: Using Patterns to Master More Complex Structures http://www.youthlearn.org/, which includes pattern-writing activities that help develop a writing style and a story structure. In addition to the journalist's questions, try using a Target Map to organize the story and develop relevant details [see Figure 1])

Other points to keep in mind:

- Decide which would work better for your story: first-person point-of-view or third-person. If the story is about something that happened to you, first-person might work best, but not necessarily. You might want to tell the story more objectively. In that case, third-person would be best.

- Is the focus of your story on "what" happened, "who" did it, "how" it happened, "where" it happened, "when" it happened or "why"? Let the focus determine which details you highlight. Not all details have equal importance. Leave out details that are not relevant.

- Think of the story as something like a miniature essay or case study. It should have a strong introduction and provide sufficient supporting detail to convince your reader to read further. But in this case, the real conclusion — the "why" — is developed in the article itself. No need to write the entire article for now, but have a sense of what you might want to say if you were actually writing it. That way you can hint at where you are going with the story and keep your reader interested.

Vocabulary/Definitions

Irony: The use of words to express something different from and often opposite to their literal meaning.

Metamorphosis: Change of form or structure; transformation.

Myth: A traditional, typically ancient story dealing with supernatural beings, ancestors, or heroes that represents the worldview of a people, explains aspects of the natural world or describes the psychology, customs or ideals of society: a creation myth.

Narrative: A story.

Pivot: To turn on, or as if on, a pivot: "The plot... lacks direction, pivoting on Hamlet's uncertainty"

Point-of-view: A manner of viewing things; an attitude; a position from which something is observed or considered; a standpoint; the attitude or outlook of a narrator or character in a piece of literature, a movie, or another art form.

Assessment

Pre-Activity Assessment

Use call-out questions or a quiz to reinforce the global warming, ozone layer, air pollution and environmental case study concepts introduced or refreshed in the introduction.

Activity Embedded Assessment

Use call-out questions or a pop quiz during the Observing and Thinking discussions (in the Procedure section) to reinforce understanding.

Post-Activity Assessment

Assess students' paragraphs on how vividly their story captures the essence of the problem and makes the reader want to read further to understand the problem better.

Activity Extensions

Learn more about how the stories we call myths have helped people throughout history to make sense of their world and deal with change. You might want to focus on myths of metamorphosis or myths of origin such as creation myths. For a brief introduction, see The Topic: Mythology (http://www.42explore.com/myth.htm) for the basics and lots of interesting links. Try some of the activities such as Make a Modern Myth. Myths are not confined to ancient times or aboriginal peoples. Can you think of examples of modern myths?

For a somewhat more challenging discussion, see Types of Myths (http://www.42explore.com/myth.htm). In what sense are myths fundamentally about the process of change?

In keeping with the themes of this activity, search the Internet for myths about frogs or salamanders. Or, read some tales of the Inuit, the remarkable people who inhabit the Arctic. Consider how their lives are changing as a result of global warming. Do the myths of the Inuit still play a role in helping them to deal with those changes?

Activity Scaling

- If necessary, students can work as "writing partners" to brainstorm story ideas and write their stories.

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things Teach Engineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!More Curriculum Like This

Students explore the causes and effects of the Earth's ozone holes through discussion and an interactive simulation. In an associated literacy activity, students learn how to tell a story in order to make a complex topic (such as global warming or ozone holes) easier for a reader to grasp.

References

Blaustein, Andrew R., and Pieter T. J. Johnson. "Explaining Frog Deformities." Scientific American 288, no. 2 (2003): 60-65. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26060165.

Dictionary.com. Lexico Publishing Group, LLC. Accessed September 6, 2020. (Source of vocabulary definitions, with some adaptation.) http://www.dictionary.com

Lamb, Annette and Johnson, Larry. The Topic: Mythology. Updated November 2000. 42eXplore.com. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.42explore.com/myth.htm

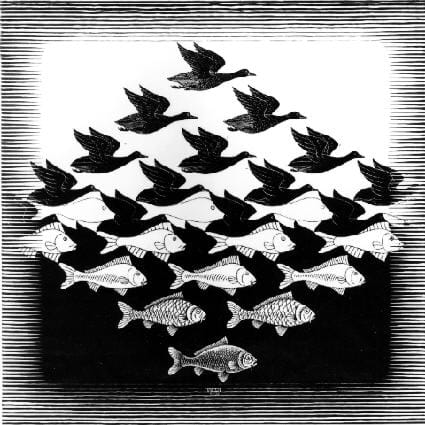

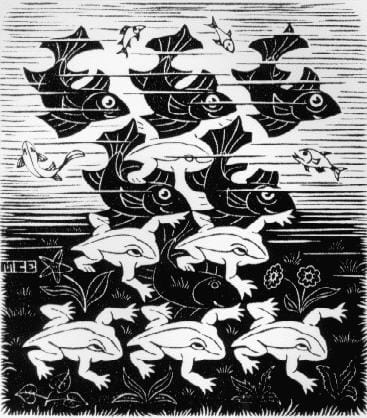

M.C. Escher: The Official Website. M.C. Escher Foundation, The M.C. Escher Company B.V. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.mcescher.com/

Storytelling and Science, Storytelling across the Arts Lesson Plans and Activities. Updated 2000. Story Arts. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.storyarts.org/lessonplans/acrosscurriculum/index.html#science

Sturm, Matthew, Donald K. Perovich, and Mark C. Serreze. "Meltdown in the North." Scientific American 289, no. 4 (2003): 60-67. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26060487.

Writing Stories: Using Patterns to Master More Complex Structures, YouthLearn Initiative at EDC. Education Development Center, Inc. Accessed September 6, 2020. (Planning guides and teaching techniques for working with youth and technology. Includes numerous activities and links. An excellent site, not to be missed.) http://www.youthlearn.org/

Copyright

© 2004 by Regents of the University of Colorado.Contributors

Jane Evenson; Malinda Schaefer Zarske; Denise CarlsonSupporting Program

Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado BoulderAcknowledgements

The contents of this digital library curriculum were developed under a grant from the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), U.S. Department of Education and National Science Foundation GK-12 grant no. 0338326. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department of Education or National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: December 11, 2020

User Comments & Tips