Summary

This activity demonstrates how potential energy (PE) can be converted to kinetic energy (KE) and back again. Given a pendulum height, students calculate and predict how fast the pendulum will swing by understanding conservation of energy and using the equations for PE and KE. The equations are justified as students experimentally measure the speed of the pendulum and compare theory with reality.

Engineering Connection

Mechanical engineers design a wide range of consumer and industry devices—transportation vehicles, home appliances, computer hardware, factory equipment—that use mechanical motion. The design of equipment for demolition purposes is another example. Like the movement of a pendulum, when an enormous wrecking ball is held at a height, it possesses potential energy, and as it falls, its potential energy is converted to kinetic energy. As the wrecking ball makes contact with the structure to be destroyed, it transfers that energy to take down the structure.

Learning Objectives

After this activity, students should be able to:

- Explain the concepts of potential and kinetic energy.

- Use the concepts of kinetic energy, potential energy and conservation of energy to perform an experiment to determine an object's velocity.

- Describe how the concepts of conservation of energy, kinetic energy and potential energy are used extensively in engineering design.

Educational Standards

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science,

technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN),

a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics;

within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

Each Teach Engineering lesson or activity is correlated to one or more K-12 science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) educational standards.

All 100,000+ K-12 STEM standards covered in Teach Engineering are collected, maintained and packaged by the Achievement Standards Network (ASN), a project of D2L (www.achievementstandards.org).

In the ASN, standards are hierarchically structured: first by source; e.g., by state; within source by type; e.g., science or mathematics; within type by subtype, then by grade, etc.

NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards - Science

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

MS-PS3-2. Develop a model to describe that when the arrangement of objects interacting at a distance changes, different amounts of potential energy are stored in the system. (Grades 6 - 8) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Develop a model to describe unobservable mechanisms. Alignment agreement: | A system of objects may also contain stored (potential) energy, depending on their relative positions. Alignment agreement: When two objects interact, each one exerts a force on the other that can cause energy to be transferred to or from the object.Alignment agreement: | Models can be used to represent systems and their interactions—such as inputs, processes and outputs—and energy and matter flows within systems. Alignment agreement: |

| NGSS Performance Expectation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

MS-PS3-5. Construct, use, and present arguments to support the claim that when the kinetic energy of an object changes, energy is transferred to or from the object. (Grades 6 - 8) Do you agree with this alignment? |

||

| Click to view other curriculum aligned to this Performance Expectation | ||

| This activity focuses on the following Three Dimensional Learning aspects of NGSS: | ||

| Science & Engineering Practices | Disciplinary Core Ideas | Crosscutting Concepts |

| Construct, use, and present oral and written arguments supported by empirical evidence and scientific reasoning to support or refute an explanation or a model for a phenomenon. Alignment agreement: Science knowledge is based upon logical and conceptual connections between evidence and explanations.Alignment agreement: | When the motion energy of an object changes, there is inevitably some other change in energy at the same time. Alignment agreement: | Energy may take different forms (e.g. energy in fields, thermal energy, energy of motion). Alignment agreement: |

Common Core State Standards - Math

-

Summarize numerical data sets in relation to their context, such as by:

(Grade

6)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Describing the nature of the attribute under investigation, including how it was measured and its units of measurement.

(Grade

6)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Fluently add, subtract, multiply, and divide multi-digit decimals using the standard algorithm for each operation.

(Grade

6)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use variables to represent quantities in a real-world or mathematical problem, and construct simple equations and inequalities to solve problems by reasoning about the quantities.

(Grade

7)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use square root and cube root symbols to represent solutions to equations of the form x² = p and x³ = p, where p is a positive rational number. Evaluate square roots of small perfect squares and cube roots of small perfect cubes. Know that √2 is irrational.

(Grade

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

International Technology and Engineering Educators Association - Technology

-

Energy is the capacity to do work.

(Grades

6 -

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

State Standards

Colorado - Math

-

Fluently add, subtract, multiply, and divide multidigit decimals using standard algorithms for each operation.

(Grade

6)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Summarize numerical data sets in relation to their context.

(Grade

6)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Solve real-world and mathematical problems involving the four operations with rational numbers.

(Grade

7)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use variables to represent quantities in a real-world or mathematical problem, and construct simple equations and inequalities to solve problems by reasoning about the quantities.

(Grade

7)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Solve linear equations in one variable.

(Grade

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use square root and cube root symbols to represent solutions to equations of the form x² = p and x³ = p, where p is a positive rational number.

(Grade

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Colorado - Science

-

Gather, analyze, and interpret data to describe the different forms of energy and energy transfer

(Grade

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

-

Use research-based models to describe energy transfer mechanisms, and predict amounts of energy transferred

(Grade

8)

More Details

Do you agree with this alignment?

Materials List

Each group needs:

- 2 stopwatches; borrow from other teachers or ask students to bring from home

- masking tape; not scotch tape

- 10 feet of string or fishing line

- heavy object or weight, to tie to string

- (if mass of heavy object is unknown) scale; one per class; groups can share

- calculator

- Swinging Pendulum Worksheet A (with algebra) or Swinging Pendulum Worksheet B (without algebra), one per student

Worksheets and Attachments

Visit [www.teachengineering.org/activities/view/cub_energy_lesson01_activity1] to print or download.Introduction/Motivation

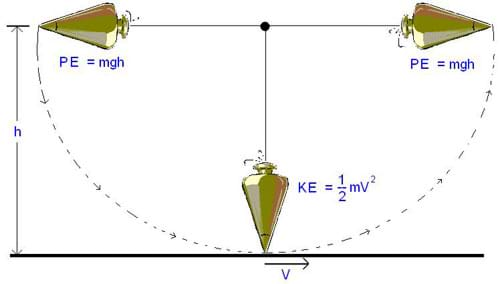

Remember that an object's potential energy is due to its position (height) and an object's kinetic energy is due to its motion (velocity). Potential energy can be converted to kinetic energy by letting the object fall (for example, a roller coaster going down a big hill or a book falling off a shelf). This energy transformation also holds true for pendulums, as illustrated in the Figure 1. As a pendulum swings, its potential energy converts to kinetic and back to potential. Recall the concept of conservation of energy—that energy may change its form, but have no net change to the amount of energy.

In this activity, you will prove that the transformation of energy occurs by calculating the theoretical value of velocity at which a pendulum should swing and comparing it to a measured value.

You will use three equations (write them on the classroom board):

PE = m∙g∙h

KE = ½ m∙Vt 2

Vm = distance ÷ time

where m is mass (kg), g is gravity (10 m/s2), h is height (meters), Vt is the calculated velocity (m/s), and Vm is the measure velocity (also m/s). To make the calculations simpler, use the metric system for measurements and calculations. This way, we can approximate gravity as 10 m/s2 and not worry about the English system's wacky units of mass.

Procedure

Before the Activity

- Gather materials and make copies of the worksheet, either Swinging Pendulum Worksheet A (with algebra) or Swinging Pendulum Worksheet B (without algebra).

- Depending on class size, designate several areas for pendulums to swing.

- Tie the string(s) or line(s) to the ceiling about 2 inches from a wall, leaving enough slack to reach the ground.

With the Students

- Divide the class into groups of four students each. Hand out the worksheet.

- Have each group measure and record the mass of its object or weight.

- Have each group pick an arbitrary height at which to release its pendulum. Limit the heights to 15 to 40 cm (.15 to .4 m) from the floor.

- Calculate the potential energy. Direct each team member to do this as a way to verify the result.

- Calculate the theoretical velocity, Vt , at the bottom of the swing.

- Remember, KE at the bottom of the swing equals PE at the top of the swing.

- If students do not know algebra yet, derive Vt for them (see the Troubleshooting Tips section).

- Have each group move to a designated area and tie its weight to the string/line so that it barely misses the ground while hanging.

- Place two pieces of tape on the wall on opposite sides of the hanging pendulum and record the distance between the two pieces.

- Set it up so the distance ranges from 30 to 50 cm (.3 to .5 m). Choose a larger distance for a higher height, that is, h = 40 cm → distance = 50 cm.

- Set it up so the pendulum rests in the middle of the two pieces of tape.

- Have one or two students pull back the weight until it reaches that arbitrary height chosen before (in step 3). Note: This should put it well beyond the piece of tape.

- Have two students synchronize two stopwatches, each holding one, and start timing as soon as the pendulum passes the first piece of tape and ending as it passes the second piece.

- The first student stops their stopwatch when the pendulum passes the opposite piece of tape and the second student stops their watch when it returns back to the initial piece of tape.

- Record both times and calculate the difference in time.

- Repeat the experiment four times so students can perform each role.

- Direct students to complete the worksheet.

- Conclude with a class discussion to share and compare results. How close were the values for the theoretical velocity and the measured velocity?

Assessment

Pre-Activity Assessment

Question/Answer: Ask the students and discuss as a class:

- Where will the pendulum have the greatest potential energy? (Answer: When it is pulled back.)

- Where will it have the greatest kinetic energy? (Answer: At the bottom/middle of the swing.)

Prediction: Ask the students to predict:

- Will pendulums at higher heights go faster or slower? (Answer: They should go faster.)

Activity Embedded Assessment

Question/Answer: Ask the students and discuss as a class:

- What happens to the potential energy as the pendulum swings down? (Answer: It turns into kinetic energy.)

- When the pendulum swings to the other side, what happens to the kinetic energy? (Answer: It turns back into potential energy.)

Post-Activity Assessment

Question/Answer: Ask the students and discuss as a class:

- If engineers can use potential energy (height) of an object to calculate how fast it will travel when falling, can they do the reverse and calculate how high something will rise if they know its kinetic energy (velocity)? (Answer: Yes, as long as you know either height or velocity, you can calculate the other.)

- For what might an engineer use this information? (Answer: Other amusement park rides besides roller coasters, or determining how high to build the next hill on a roller coaster, or how to launch something, etc.)

Safety Issues

Make sure students do not use the weighted pendulum to swing at other students.

Troubleshooting Tips

If students have not learned algebra yet, use the Worksheet Version B with Vt already derived.

An approximation is used for calculating measured velocity, Vm . If the tape markers are too far apart, the approximation will not hold true. However, if they are too close together, it may be difficult for students to clock a difference in time. The distance should range from 30 to 50 cm (.3 to .5m). Choose a larger distance for a higher height; that is, h = 40 cm → distance = 50 cm.

Activity Extensions

So far, students have calculated the mechanical energy when it is either completely potential or kinetic energy. What about when the mechanical energy is composed of both? Assign students to create a table and/or graph (depending on their skill level) showing the potential and kinetic energies of their pendulum at heights of 0, ¼h, ½h, ¾h, and h. (Hint: They already know the values at heights 0 [purely kinetic] and h [purely potential].)

Activity Scaling

- For lower grades, work through the calculation of average time. Also, explain and derive Vt for them and use Worksheet B, the version without algebra.

- For upper grades, use Worksheet A, with algebra.

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things Teach Engineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!More Curriculum Like This

This activity shows students the engineering importance of understanding the laws of mechanical energy. More specifically, it demonstrates how potential energy can be converted to kinetic energy and back again. Given a pendulum height, students calculate and predict how fast the pendulum will swing ...

Students are introduced to both potential energy and kinetic energy as forms of mechanical energy. A hands-on activity demonstrates how potential energy can change into kinetic energy by swinging a pendulum, illustrating the concept of conservation of energy.

High school students learn how engineers mathematically design roller coaster paths using the approach that a curved path can be approximated by a sequence of many short inclines. They apply basic calculus and the work-energy theorem for non-conservative forces to quantify the friction along a curve...

Imagining themselves arriving at the Olympics gold medal soccer game in Rio, Brazil, students begin to think about how engineering is involved in sports. After a discussion of kinetic and potential energy, an associated hands-on activity gives students an opportunity to explore energy-absorbing mate...

Copyright

© 2004 by Regents of the University of ColoradoContributors

Chris Yakacki; Malinda Schaefer Zarske; Denise W. CarlsonSupporting Program

Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado BoulderAcknowledgements

The contents of this digital library curriculum were developed under grants from the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), U.S. Department of Education and the National Science Foundation (GK-12 grant no. 0338326). However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department of Education or National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: August 11, 2023

User Comments & Tips